Deadly Galerina Study

On Saturday morning, I was out supporting a Mushroom I.d. walk with Luke Eckstein, who is one of the most knowledgeable, and approachable mycologists I have ever met. He knows his fungi and he has a welcoming approach which I really appreciate. He is kind, funny, and eager to share a passion of his which really makes for a good teacher. This was the 2nd year I have done a Mushroom walk with him. The previous year my partner and I went to his mushroom walk and we learned a lot. I remember being amazed by the amount of mushrooms he saw and knew, and could fill us in on a bit of the natural history of.

One mushroom he identified last year, and this year, and which I found today at work was the Deadly Galerina (Galerina marginata). I decided that I wanted to learn as much as I could about this species as they were a hazardous species which I may encounter on the daily with my students. I feel like if I know all of the poisonous species right off the bat, then if I make mistakes with benign/harmless species, then it won’t be as big a deal than if I made that same mistake with the poisonous ones. Make sense? Know the things that will kill you, and then you can take the time to learn more comfortably, and more forgivingly with the harmless ones.

So here is my study of the Deadly Galerina. I hope you enjoy!

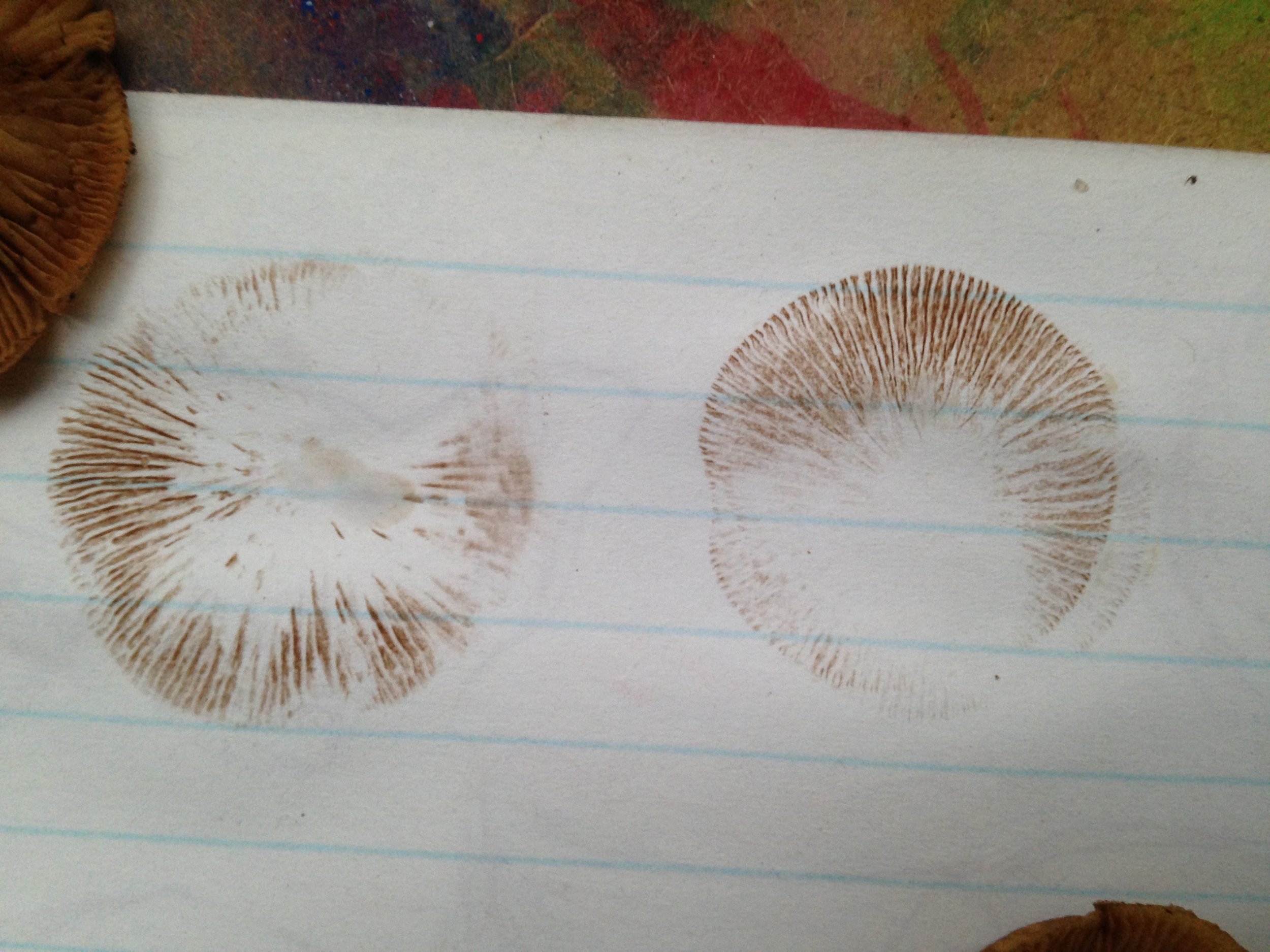

Galerina marginata or Galerina autumnalis are synonyms for the Deadly Galerina. Other common names include Funeral Bells. I have found them growing in scattered singly or clustered in groups along rotting hardwood or conifer logs, usually in the fall though I have heard they also grow in the Spring. Caps are 2.5 - 6 cm in diameter, convex/bell shaped when young, flatter as they age with a slight bump or "umbo" in the middle. Ochre to tan-rusty-brown with a striate, or striped margin. The gills are close, but not crowded, yellowey-brown and attached at the stipe (stalk). The stipe is hollow, 30 - 90 mm L x 3 - 10 mm W. There is often sign of a pale ring along the stipe though the ring may be absent. Spore print is brown.

This species is both common and abundant, distributed widely. On inaturalist.org, Deadly Galerinas are found throughout Turtle Island (North America), along the West coast of South America, throughout Europe, South Africa, on the East coast of Australia, New Zealand, India, Japan, Vietnam and some other spots. A pretty cosmopolitan distribution.

This toxic mushroom contains amatoxins. These amatoxins seem to only be damaging if ingested or encountered in the bloodstream. In 2013, a study on Mice reported that there was no absorption of amatoxins through the skin of the Mice, and therefore no toxic effects, but I couldn't read the whole paper to find out more details. The name amatoxin comes from the occurrence of this toxin in the Amanita genus of mushrooms.

While the research I have done seems to vary considerably I have read that small amounts of these mushrooms could kill. It is these amatoxins which enter the bloodstream and damage internal organs, but it's really the damage done to the heart, kidneys and especially the liver which is likely to kill you (its the first organ the toxins encounter after being digested). They are taken up in the liver, and then excreted through bile into the blood, then back to the liver, causing a cycle of poisoning. The amatoxins break down cell walls. If the cells in the liver or heart are damaged, this can cause the cells to breakdown quickly and cause the liver or heart to dissolve. The acute symptoms can include headache, nausea, coughing, diarrhea, and lots of peeing. After about 12-24 hrs, there is an eye of the storm moment where all appears to be well, but after this second 12-24 hr period of calm, the liver and kidneys start to fail, and death can happen on the second day after being poisoned. There have been cases of survival from around the world, but it seems measured by the amount of deaths associated with these mushrooms.

Amanita muscaria var. Guessowii @ Pine Plantation near Muskrat Pond, 2021.07.05

Other species of mushrooms which contain amatoxins include Death Cap (Amanita phalloides), Eastern Destroying Angel (A. bisporigera), and trace amounts in Fly Agaric (A. muscaria).

G. marginata is a white rot fungi meaning it breaks down all three main components of wood : lignin, cellulose and hemicellulose. Typically, in the later stages of decay by white rot, all that’s left are long stringy fibers of cellulose. I have grabbed handfuls of logs which are being broken down by the white rot and squished the remaining fibers to the point where liquid comes out. These fibers are hydrophilic (meaning they uptake and hold water easily). This contributes to the overall moisture levels in the soil surrounding the rotting log.

While researching the G. marginata I found a couple of comparisons to the Honey Mushrooms (Armillaria spp.). I don’t know if I have yet encountered Honey Mushrooms so I do not have much experience but I looked into differences in characteristics which might aid in identification.

Honey Mushrooms, especially Armillaria mellea, are slightly yellow to brown with a cap which appears tan to yellowy brown, with dark hairs or scaly flecks, especially towards the center of the cap. They tend to grow in groups or clumps, though occasionally singly, on dead or live wood, or while decaying the roots on living trees. The gills are usually white, though may brown slightly as they age. There is a ring along the stipe remnant of the partial veil which covers the gills on the underside of the cap when the Honey Mushroom was young.

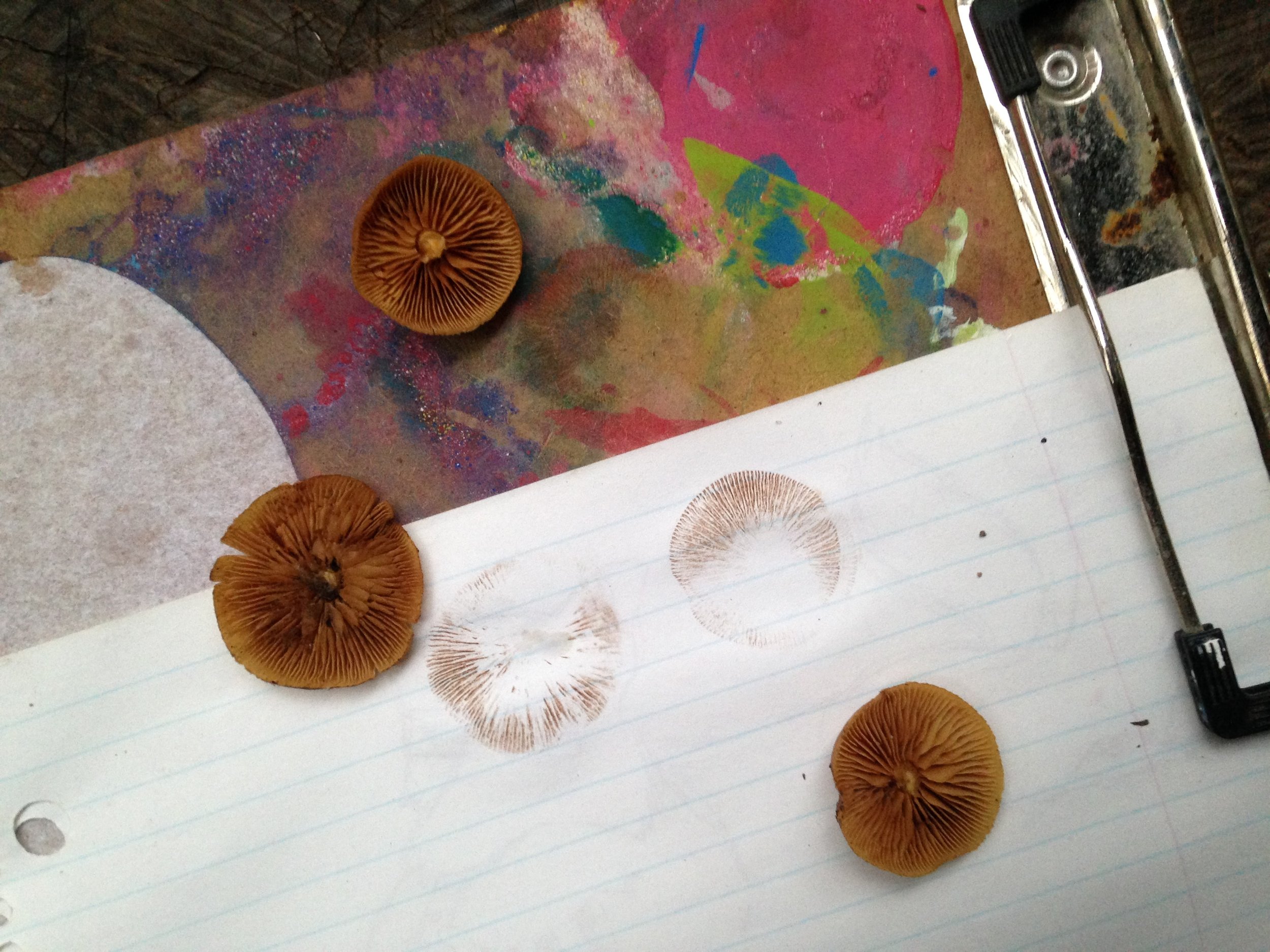

The biggest features which help to tell the G. marginata and the A. mellea (and other Armillaria species) apart are the colour of the spore prints. G. marginata has a rusty-brown spore print while the A. mellea supposedly has a white spore print. While, as mentioned above, I have not encountered a Honey Mushroom, I did have the chance to try a spore print with the G. marginata.

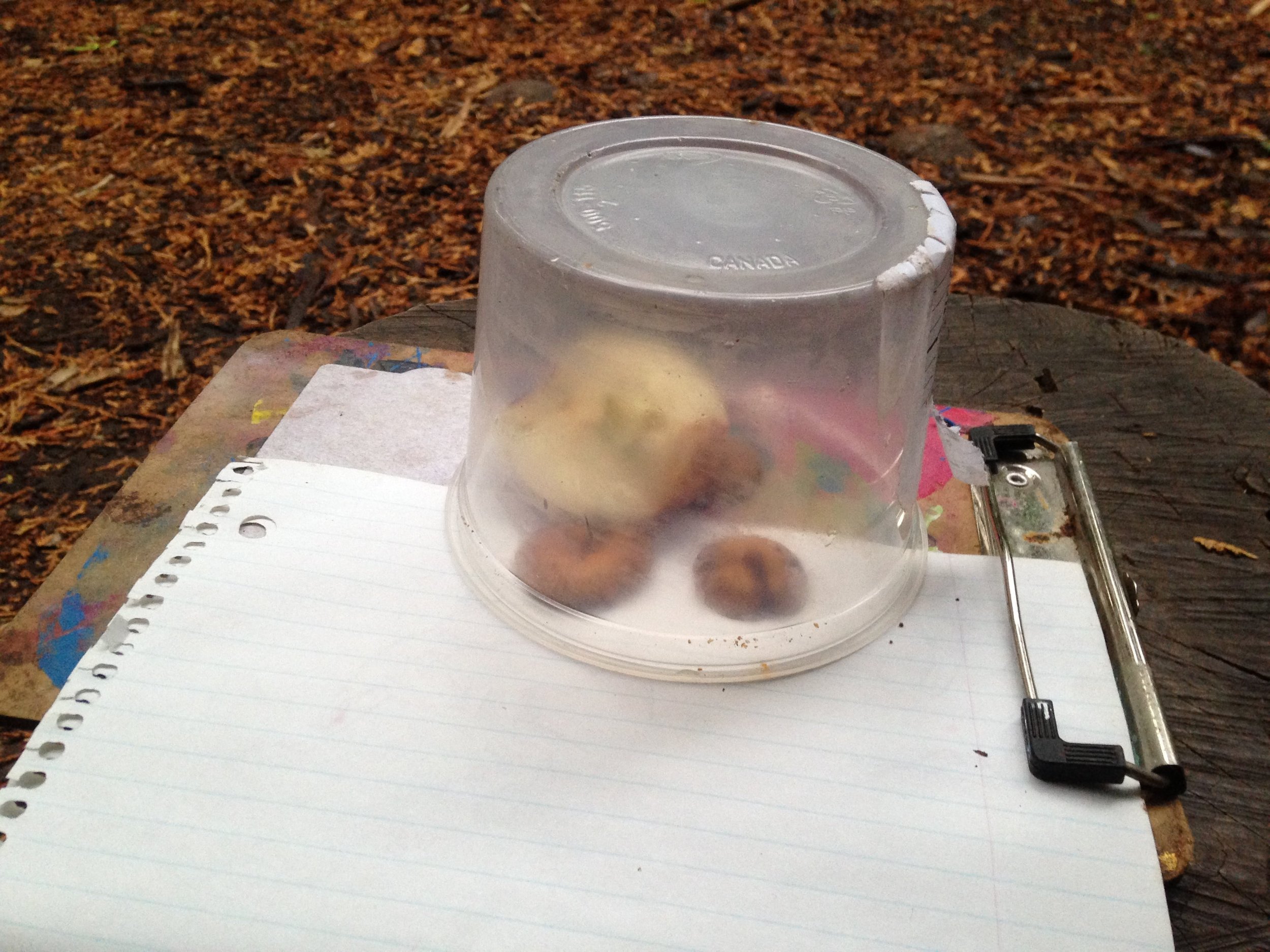

I removed the caps from three mushrooms and placed two of them on a piece of paper which was lined with blue ink attached to a brown clipboard covered in paint splotches. I placed the third on the directly onto the clipboard with the paint splotches. My hope was that if the spore prints were brown they would show up clearly on the white paper, and if white, they would show up on the colourful clipboard. I left the caps covered by an old container base with half of an Apple (Malus domesticus) tucked inside to ensure a humid environment to encourage spore release. I placed the set up on top of a shelf in a breezy prospector tent and left them to sit for approximately 20 hrs. When I checked in on the clipboard the following morning I noted brown spore prints had shown up on both the paper and the clipboard beneath all three caps.

With Luke’s help with primary identifications, all the research, and the spore prints, I would conclude for certain that who I found and have been studying have certainly been Deadly Galerina. I am grateful for getting the chance to get to know another being in my broad community. This was done through careful noticing of habitat, colour, form, spore prints, reading field guides, papers, watching videos, reviewing photographs, and visitations, some repeated, to specific sites to observe the mushrooms themselves. I am grateful for being in a part of the world where I can spend time observing other life forms and lucky enough to get to do this exploration with friends and colleagues. It’s always great to make new friends.

To learn more :

Honey Mushroom & Deadly Galerina - Identification and Differences with Adam Haritan

Amatoxin entry at Wikipedia

Polypeptide toxins in Amanita Mushrooms : Cornell College of Agriculture and Life Science

Amanita muscaria: chemistry, biology, toxicology, and ethnomycology

Dermal absorption and toxicity of alpha amanitin in mice

Amatoxins in Wood-Rotting Galerina marginata