Draw a mouse. Go to jail. This seems to be Disney’s personal motto. The Walt Disney Company, one of the largest media conglomerates in the world is very well known for its children’s movies and lovable characters (Levin, 2004). The uplifting and family oriented company that The Walt Disney Corporation has made themselves out to look like is a facade, in actuality they are one of the most powerful corporations in the world. Often times the corporation has been notorious for enforcing their copyrights when dealing with others who have attempted to use their ideas or their characters, no matter who it is. This is the case with a group of underground cartoonists known as the Air Pirates. In 1971 they put out a comic book parody of Disney cartoons in which Mickey Mouse, Minnie Mouse, Goofy and other Disney characters were drawn doing illegal narcotics, intercourse, using profanity and participating in other compromising activities (Levin, 2004). Disney did not appreciate the use of their characters, especially in the state that they were being drawn in; they quickly took action against the renegade group. Although this was not the first copyright issue that Disney has had to deal with it was certainly one of the largest and most controversial. But, Disney is not always the innocent one in copyright cases they have also been known to utilize the ideas of others as well, accept they can afford to pay the penalty for doing so.

The Walt Disney Corporation was created by Walt Disney himself. In 1918 after failing to enlist into the army along with a number of other careers Walt began to pursue a career in commercial art. This soon led to his first experiments in animation. He began producing short animated films for local businesses, in Kansas City (Smith, 2011). By the time Walt had started to create The Alice Comedies, which was about a real girl and her adventures in an animated world, Walt ran out of money, and his company went bankrupted (Smith, 2011).. Instead of giving up, Walt packed his suitcase and with his unfinished print of The Alice Comedies in hand, headed for Hollywood to start a new business After the Alice Comedies failed Walt took a chance in cartoons and animation in which his line of failures would soon come to a halt (Smith, 2011). On November, 1928, six months prior to sound being introduced to the motion picture industry Mickey featured in the unfinished test cartoon Plane Crazy. After sound was finally introduced to the business Mickey Mouse made his debut in Steamboat Willie as the world’s first synchronized sound cartoon (Smith, 2011). Steam Boat Willie was an instant hit with the viewers. People from all parts of the world were soon familiar with the mouse and over the years Disney evolved into a very iconic piece of American history, recognized by all. Mickey has been the front for this Company and is still the most valuable character that The Walt Disney Corporation has produced by far.

The original Air Pirates were a gang of Mickey Mouse antagonists of the 1930s; O’Neill regarded Mickey Mouse as a symbol of conformist hypocrisy in American culture, and therefore a ripe target for satire (Air Pirates, 2011). In 1971 he gathered up a group of young cartoonists calling themselves The Air Pirates who collectively deciding to put Disney to the test (Mickey Mouse, 2011). The group’s founder Daniel O’Neil was a cartoonist known for his comic strip The Odd Bodkins in the San Francisco Chronicle. Other members of The Air pirates included Bobby London, Gary Hallgren,Ted Richards and Shary Flenniken, who was the only member not to be sued for their Disney parodies (Air Pirates, 2011). Only two issues of The Air Pirate Funnies were distributed. The first issue was dated July 1971, and the second issue of Air Pirates Funnies dated August of that year. Both were published under the Hell Comics imprint, and were distributed through Ron Turner’s Last Gasp publishing company (Air Pirates, 2011). The comics featured Multiple Disney character such as Mickey Mouse, Minnie Mouse, Pluto, Goofy, Donald duck and many other characters engaging in inappropriate behaviors. Such behaviors included the use of narcotics, the use of profanity and the characters engaging in sexual acts such as intercourse. Concerned that changing the names of the characters would take away something from the parody, the group decided to leave the names of the characters the same as they already were. In the video RiP: A Remix Manifesto by Brett Gaylor he explores the different trials and tribulations when dealing with copyright. O’Neill makes an appearance in the video and defends the actions of The Air Pirates by stating that Disney provided all the materials necessary. Meaning, Disney had published books on how to draw all of their characters which is what the underground cartoonist used for their comics (Gaylor, 2008). For The Disney Corporation the fact that they published the drawing books was irrelevant. They were not only upset by the fact that The Air Pirates had infringed upon their copyright but for the way that their lovable children’s characters were being portrayed. They believed that what they were producing could corrupt the image that the characters represented and ultimately effect there profit. O’Neill was so eager to be sued by Disney that he had copies of Air Pirates Funnies smuggled into a Walt Disney Company board meeting by the son of a board member (Air Pirates, 2011).

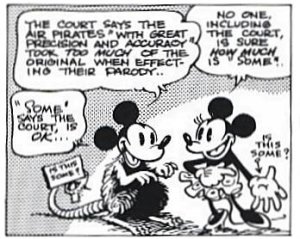

On October 21, 1971 Dan O’Neill got his wish as Disney filed a lawsuit alleging, among other things, copyright infringement, trademark infringement and unfair competition against O’Neill, Hallgren, London and Richards,Turner’s name to the suit. The Pirates, in turn, claimed that the parody was fair use (Air Pirates, 2011). With all the different members from both sides of the spectrum it is difficult to find an accurate retelling of the events which occurred throughout the lawsuit although it has been said that O’Neill was insolent. The initial decision was made by Judge Wollenberg on July 7, 1972 in the California District Court. The decision went against the Air Pirates. O’Neill’s lawyers appealed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. It was at this time that O’Neill confronted The Air Pirates about going forward with the case on his own. Hallgren and Turner settled with Disney, but London and Richards decided to continue fighting (Air Pirates, 2011). In order to have money for The Air Pirates defense fund the group began selling off original art work and other novelties to add to the fund.

While in the middle of the legal proceedings The Air Pirates were in violation of the temporary restraining order on them, they published some of the material intended for the third issue of The Air Pirates Funnies in the comic The Tortoise and the Hare. Nearly 10,000 issues were soon confiscated under a court order. In 1975, Disney won another restraining order and a preliminary judgment of $200,000. O’Neill defied this restraining order as well by continuing to draw Disney parodies (Mickey Mouse).

The case continued to be dragged on for several more years. Finally, in 1978, the Ninth Circuit dismissed the trademark infringement claims and ruled against the Air Pirates three to zero for copyright infringement. In 1979 the Supreme Court refused to hear an appeal from The Air Pirates. O’Neill made it a point to announce his plans from the very beginning of the battle with Disney. He insisted that he wanted to lose initially, then appeal it again, then to lose yet again and to continue drawing his parodies until eventually the courts were forced to either throw him in jail or allow him to continue to draw his cartoons. As O’Neill put it, “Doing something stupid once is just plain stupid. Doing something stupid twice is a philosophy” (Air Pirates, 2011).

Daniel O’Neil later went on to produce his own four page Mickey Mouse story called Communiqué #1 from the Mouse Liberation Front which appeared in the magazine CoEvolution Quarterly (Air Pirates, 2011). Following the next year O’Neill recruited a number of diverse artists for this “secret” artist’s organization The Mouse Liberation Front art show was then later displayed in New York, Philadelphia and San Diego. O’Neill delivered The M.L.F. Communiqué #2 in person to the Disney studios with the help of some of the sympathetic Disney employees. The main feature of the meeting was a drawing of Mickey Mouse allegedly smoking a joint in the late Walt Disney’s office (Air Pirates, 2011).

In 1979 Disney asked the court to hold Daniel O’Neill in contempt and have him prosecuted criminally, along with Stewart Brand who was the publisher of CoEvolution Quarterly at the time. Then later in 1980, after an unrecoverable sum of $190,000 in damages coupled with the $2,000,000 in legal fees also against O’Neill due to his continual disregard for the court’s decisions (Air Pirates, 2011). The Walt Disney Company ended up settling the case. They promised not to enforce the judgment as long as the Pirates no longer infringed Disney’s copyrights and dropped the contempt charges (Air Pirates, 2011).

In a number of interviews about the events with Bob Levin for his book The Pirates and the Mouse: Disney’s War against the Counterculture. Bob asks O’Neill about his opinions on the final decision of Disney and the courts. For Dan O’Neill after multiple accounts of disregarding the courts decisions he discloses that the victory is deemed a win for two main reasons. The first reason that he considers the final decision a conquest is that he never went to jail for his actions. He does not consider the financial penalties as a deterrent. The second part of the win was connected to Daniel’s old comic strip the Odd Bodkins (Levin, 2004). It was a very successful cartoon and eventually it was picked up by the syndicate but, as the cartoon became more and more controversial. The publishers ended up wanting to withdraw it from the paper. When O’Neill was younger after it’s withdraw from the paper he wanted to publish a book of the comic strip (Levin, 2004). While in the process of doing so he discovered that they actually owned the copyright. He originally thought that he owned the rights to the strip and was upset and surprised to find out that the San Francisco Chronicle owned them. So, before the Disney lawsuit he figured out a way to finally acquire the rights to the Odd Bodkins. He utilized his ability to draw Disney characters and started putting them into the background of the comic. It eventually got to the point where he was using over twenty-eight Disney characters in total (Levin, 2004). Throughout everything that was happening with The Air Pirates and their battle against The Disney Corporation O’Neill told the syndicate that since they owned the strip, the suit should be against them and that they would have to be the ones to defend against Disney (Levin, 2004). They ended up forfeiting their copyright and giving all of the rights back to O’Neill. He has since utilized these rights to continue writing the comic strip and even publish a website for it. After everything with The Walt Disney Corporation settled and O’Neill promised not to publish any more Disney cartoons he still manages to include some little hints of the character in the Odd Bodkins (Levin, 2004).

Even though Walt Disney originally stole the idea for the original cartoon in which Mickey was first introduced from Steam Boat Bill Junior with no form of recognition the corporation is quick to defend their rights from anyone who tries to use their material. Although they ultimately settled and dropped the issue the outcome has not deterred them prosecuting others who have since then attempted to use their ideas. Daniel O’Neil has come out of the issue with all that he planned to eventually acquire from before The Air Pirates were even assembled. The whole situation with The Air Pirates and The Walt Disney Corporation goes to show of the importance of having a copyright. The case remains very controversial. Although Disney has had the copyright extended on multiple occasions the real issue came after the case was finished. Because of instances like this copyright issues have become more predominant and it has become more and more difficult to classify something as a parody or fair use. So although some people are glad to see that corporations like that are not as untouchable as previously believed, there are those who remain perturbed at the fact that it has made copyright issues more predominant and difficult to defend.

Work Cited

“Air Pirates.” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. 13 Mar. 2011. Web. 22 Apr. 2011. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Air_Pirates>.

“Copyright.” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. 13 Apr. 2011. Web. 22 Apr. 2011. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Copyright>.

Gaylor, Brett. “RIP!: A Remix Manifesto.” External Sites – NFB. 2008. Web. 22 Apr. 2011. <http://films.nfb.ca/rip-a-remix-manifesto/>.

Levin, Bob. “Dan O’Neill.” Edward Samuels. 2004. Web. 22 Apr. 2011. <http://www.edwardsamuels.com/copyright/about/anecdotes/oneill.html>.

“Liblicense: Definitions of Common Words and Phrases.” Yale University Library. May 2008. Web. 22 Apr. 2011. <http://www.library.yale.edu/~llicense/definiti.shtml>.

“Mickey Mouse.” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. 20 Apr. 2011. Web. 22 Apr. 2011. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mickey_Mouse#Walt_Disney_Productions_v._Air_Pirates>.

Smith. “Walt Disney: Long Biography.” Walt Disney – Just Disney.com – Your Source For Disney. Web. 22 Apr. 2011. <http://www.justdisney.com/walt_disney/biography/long_bio.html>.

“Steamboat Willie.” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. 13 Apr. 2011. Web. 22 Apr. 2011. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steamboat_Willie>.

“The Purpose and Importance of Copyright Law.” Law Office of K.D. Long. 9 Feb. 2009. Web. 22 Apr. 2011. <http://klonglaw.com/?p=124>.